From Zero to Trust in 1.2sec – F1 Zero Trust Challenges

F1 is not about racing

From Zero to Trust in 1.2sec - F1 Zero Trust Challenges.

When watching a Formula 1 weekend that consists of three days of high-speed driving (practice, qualifying and the actual race), one would come to the natural conclusion that the sport is about racing.

And while, yes, that is true, there is much more to F1 than just racing. In fact, today, the sport is almost entirely based on maths and science.

Not only are maths and science crucial to a Grand Prix weekend, but are also the backbone on which the industry’s innovation relies – and F1 is one of the most innovative industries in the world.

The need for speed (and data)

When it comes to the contribution of maths and science to the race itself, every move in F1 racing is calculated; every millisecond counts – the difference between the fastest and second fastest driver is often less than a second – meaning performance is crucial.

So, naturally, teams seek to outperform their competitors (it is a competitive sport at the end of the day). To make accurate calculations and decisions, F1 teams rely on data. Data is everything in F1 racing, which is why each vehicle is equipped with around 150-300 sensors generating roughly 300MB of data per weekend.

However, data collection starts long before the race and continues long after; data collection occurs pre-, during, and post-race. Pre-race simulations provide data that is analysed to develop the racing strategy. During the race itself, the data transmitted from the vehicle is analysed in real-time to ensure top performance – both on the track and in the pit lane – by making visible aspects of the race that are otherwise invisible. Engineers and pit crew at the paddock use the data to understand the car’s trajectory, engine performance, airflow, even the driver’s responsiveness, and more. This allows for real-time decision making on the track and off it, knowing when and, more importantly, why a car needs to make a pit stop.

F1 cars fly around the racecourse more than 50 times at speeds surpassing 200mph, so it is common for problems to arise mid-race. When an issue does occur, the data determines exactly where it stems from, allowing the pit crew to make the necessary changes during a pit stop. And if you have ever seen an F1 pit stop, you know just how quickly those changes are made.

Data plays a vital role in post-race analysis to advance the actual business of the team. The main job of a Formula 1 team is to design and develop the car that the drivers will race. Data helps engineers make the necessary improvements and adjustments to enhance performance and, ideally, outperform the other cars on the track. The F1 industry is also known for its innovations, of which data is a significant contributing factor. By analysing the copious amounts of data generated, F1 teams have innovated in ways that permeate into other industries – did you know that the McLaren team has helped speed up toothpaste production?

Of course, all this data means F1 teams are a valuable target for malicious actors for several reasons. As F1 racing is a competitive sport, team rivalry is a given. And, in some cases, the rivalry goes beyond the track. It is not implausible to suggest that teams might conduct espionage on one another to gain a competitive advantage. In fact, the 2007 Spygate controversy centred on just that; a former Ferrari engineer was accused of passing on almost 1,000 pages of highly confidential technical data to McLaren’s chief designer at the time.

Competitors, however, are not the only potential adversaries. An F1 team could be a target to anyone, depending on the perpetrator’s motive. Financial reward is a primary motivating factor among cybercriminals, while others might want to make a statement or simply gain recognition. Whatever the motive, the teams’ reliance on data means that an attack impacting such data can have damaging consequences. In 2014, the Murassia F1 team found itself victim to a trojan virus that caused an entire day of testing to be lost. And, as we know, in F1 racing, a day’s worth of data is, to us, equivalent to a year’s worth of data.

Three, two, one, zero…trust

The Formula One World Championships, as the name suggests, is a global operation. With Grand Prix races occurring in more than 20 countries, teams have to relocate for every event. This, and the fact that the team has a permanent home base, means that data is being transmitted internationally across several dispersed entry points, thereby significantly expanding the teams’ attack surface. There is danger on and off the track. To protect their networks and data, F1 teams should, if they have not already, consider adopting the Zero Trust (ZT) security model. In doing so, the trust that was once automatically given to internal users and devices is eliminated to protect against threats occurring within the enterprise environment.

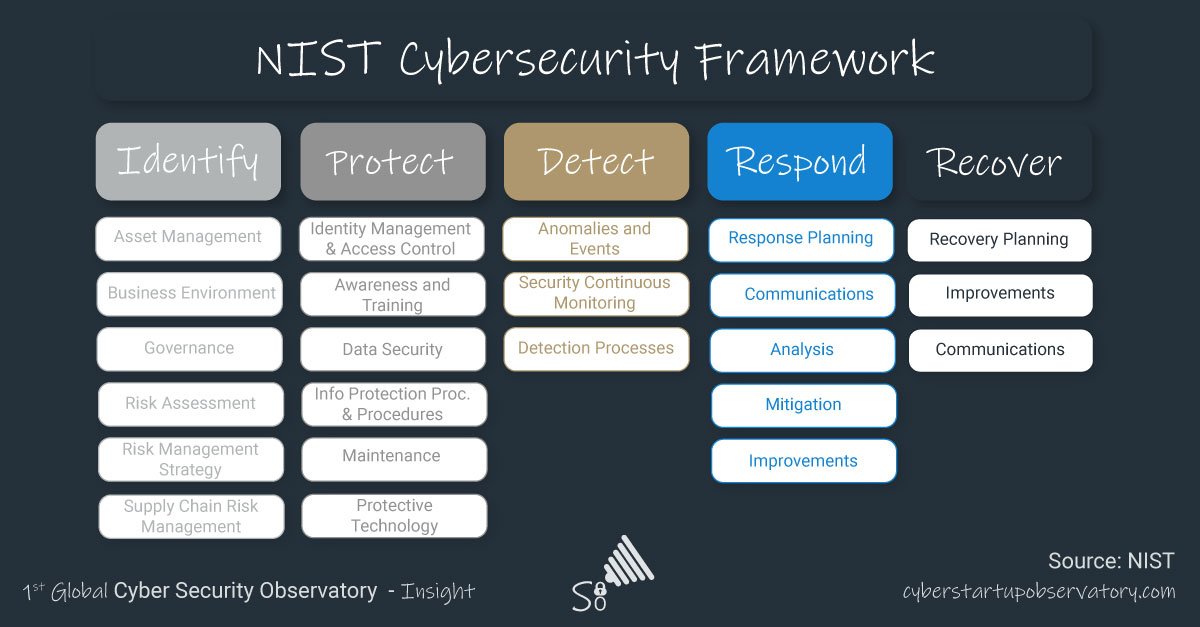

As attackers can easily infiltrate an organization, it quickly became apparent that perimeter-based network security is insufficient. So, with ZT, every user and device is treated as untrusted every single time. The Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA) enforces various security protocols to restrict network access, including the principle of least privilege and micro-segmentation. In addition to limiting network – and, subsequently, data – access, such features also assist in reducing the blast radius of an attack, should there be one. Access policies support the architecture in making access decisions.

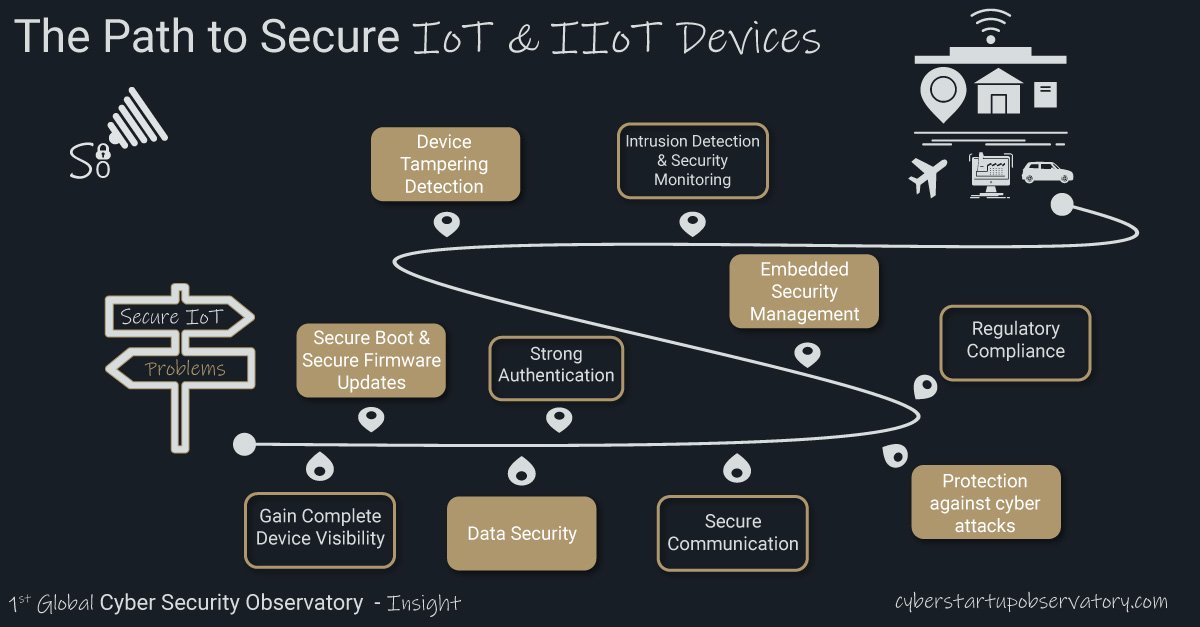

Ironically, the greatest limitation of ZT relates to data. Since ZT is not a security tool itself but rather a data-based security model, it relies on other security tools to provide the necessary data to carry out its overall function. One such data source is identity management, which includes device identity. However, a device’s identity might not be accurate due to a lack of Physical Layer visibility. No existing security solution covers the Physical Layer, meaning the device’s Physical Layer information is not captured, posing a threat to accurate device validation. If device information is incomplete, then device validation will be, please excuse me, invalid, having a spillover effect on the accuracy of access decisions.

Cybercriminals, of course, are exploiting this vulnerability of ZT by carrying out hardware-based attacks. Such attacks make use of Rogue Devices; tools which, by design, act maliciously. Spoofed peripherals impersonate legitimate HIDs and, having been manipulated on the Physical Layer, raise no security alarms as endpoint security solutions do not differentiate between the spoofing device and the legitimate one.

Network implants go completely undetected as they sit on the Physical Layer, thereby running under the radar of network security tools, including NAC. With Rogue Devices triggering no security concerns, attackers can gain unauthorized access to the target network and even bypass the ZT security protocols of the principle of least privilege and micro-segmentation. As a result, the attack surface increases as malicious actors can move laterally across the network. So, I should correct myself when I suggest that F1 teams adopt a ZT approach; they should adopt a Zero Trust Hardware Access approach.

Zero Trust Hardware Access with Sepio Systems

Sepio Systems’ Hardware Access Control solution (HAC-1) provides organizations with protection at the hardware level by covering the Physical Layer. In doing so, organizations benefit from complete visibility of all hardware assets operating on both USB and network interfaces. All IT, OT and IoT devices – whether they are managed, unmanaged or hidden – are instantly detected and identified by the solution.

Through Physical Layer fingerprinting and Machine Learning, the solution calculates a digital fingerprint of all hardware assets and compares this with known fingerprints to identify vulnerable and malicious devices. In addition to the deep visibility layer, a comprehensive policy enforcement mechanism recommends on best practice policy and allows the administrator to define a strict, or more granular, set of rules for the system to enforce.

When a device breaches the pre-set policy, or is identified as malicious, HAC-1 automatically instigates a mitigation process that instantly blocks unapproved or Rogue hardware. With such capabilities, HAC-1 prevents attackers from bypassing ZT protocols with Rogue Devices before they even try. In other words, Sepio Systems provides protection at the first line of defence.

With the HAC-1 solution deployed, F1 teams can focus on what they do best without worrying about malicious actors infiltrating their network through hardware-based attacks. Just as quickly as they are doing their pit stops, HAC-1 is detecting malicious and vulnerable devices – it is in the blink of an eye.

Follow Us

From Zero to Trust in 1.2sec – F1 Zero Trust Challenges